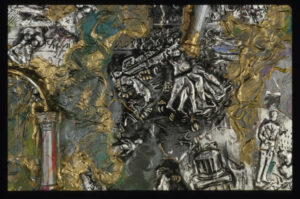

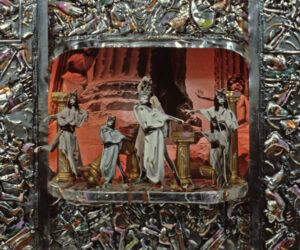

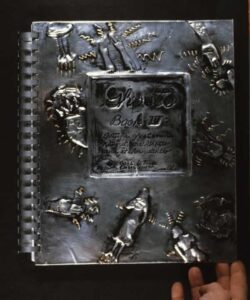

In works such as ‘Great Goddess House Shrine’ (1982), Jane Gilmor set ancient feminine symbols from Catal Huyuk in a copper repousse altar, which enclosed a video of a ritual she performed. She suggests that the altar’s first use as a sacred site for sculpted images of the Great Goddess could be reconfigured —resacralized as a place for modern-day video images of the Goddess within herself.

Kay Turner, Beautiful Necessity: The Art and Meaning of Women’s Altars Thames & Hudson, 1999, (pg 74, ill pg 74, pg 91)

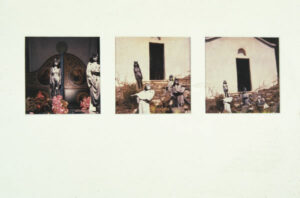

The photo tableaux and wall shrines by Jane Gilmor present such a startling collision of kitsch with myth that one may not know whether to chuckle or recite incantations. A masterful mélange of the modern and the ancient, Gilmor’s motivations lie in the “construction and deconstruction of myth;” her great goddesses enact sacred rites in the ruins of temples, counterparts to the rituals that must have once taken place there in honor of mythological deities. The feline headed personae, reminiscent of vestal virgins or a kitty chorus for a Greek tragedy, appear on her sculptural assemblages and shrines engaging in their enigmatic sacraments, in miniature, in relief, in photos, and on video. These works question all that we associate with modern religious pomp and circumstance, the solemnity of which seems a far cry from the objects created and performances staged by Gilmor, which blend a ceremonious melodrama with a healthy dose of satire

Paul Brenner, assistant curator Great Goddesses: Sculpture and Photo Tableaux by Jane Gilmor Real Art Ways, Hartford, Ct. 1988

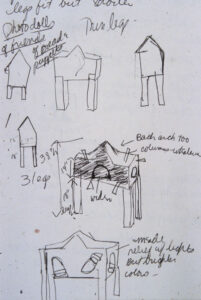

During the 1970’s and early 80’s, I combined metal repoussé with video, film and photo documentation of my performance tableaux in Greece, Egypt, Asia, and Iowa. The forms of the smaller wall shrines and the larger works using video and film are inspired by the roadside shrines of rural Greece, Turkey, and Italy A recurrent theme on both the relief metal surfaces and the video and photo images incorporated into them is a questioning of cultural myths about women. These shrine-like sculptures are reminiscent in form to the vernacular folk architecture of rural Greece and Mexico where I traveled and documented roadside religious structures in the mid and late 1970’s. Indeed these objects are intended to create a ritualistic ambience not unlike that of some bizarre roadside shrine. In these works I am in the deeper relationships between myth, experience, and culture. For me these structures and installations functions as shrines to the mythic potential of ordinary life, embodying its most peculiar, ridiculous, and meaningful (less) qualities.