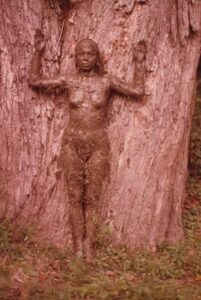

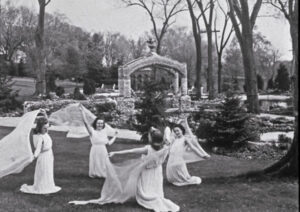

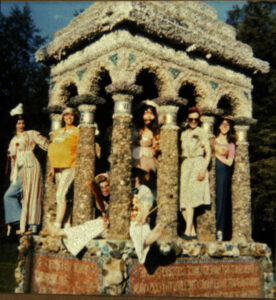

Following the 1976 All-American Glamour Kitty Pageant event and subsequent installations, and paintings, I adopted a cat-masked Isadora Duncan-like altar ego based on my research of ancient imagery associating “the feminine and the feline” with women and goddess archetypes. During the late 1970’s and early 80’s I took students to ancient sites in Greece, Egypt, Turkey, and Italy. There we staged a series of photo tableaux images and live performances. These performances were partially concerned with the construction and deconstruction of myths about women. In later work these animal hybrid goddesses also served to parody gender-related roles.

As a member of the Women’s Art movement of the 1970’s I worked alongside friends and colleagues such as Ana Mendieta and Mary Beth Edelson to visualize the female psyche as a strong creative force. Many of these images were used in Lucy Lippard’s traveling lectures on the topic and in her book, OVERLAY: Contemporary Art and the Art of Pre-history, Random House, 1983 and later in Broude and Gerrard’s The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970’s History and Impact, Abrams, 1994. Indeed, these performance tableaux both embrace and question the notion of female goddess archetypes in both past civilizations and the then current Women’s Art Movement (1970’s). Elements of ritual and melodrama compound the confusion. Are these images satire or worship of a goddess archetype – or both?

Comments from reviewers:

The photo tableaux by Jane Gilmor present such a startling collision of kitsch with myth that one may not know whether to chuckle or recite incantations. When Erma confronts the Great Goddess, one can’t help but wonder what each must be thinking about the other. A masterful m�lange of the modern and the ancient, Gillmor’s motivations lie in “construction and deconstruction of myth;” her great goddesses enact sacred rites in the ruins of temples, counterparts to the rituals that must have once taken place there in honor of mythological deities. The feline- headed personae, is reminiscent of vestal virgins or a kitty chorus for a Greek tragedy. As both Goddess and worshipers, these characters parody the animal associations with gender that we have come to adopt at face value in contemporary society. These works question all that we associate with modern religious pomp and circumstance, the solemnity of which seems a far cry from the performances staged by Gilmor, which blend a ceremonious melodrama with a healthy dose of satire.

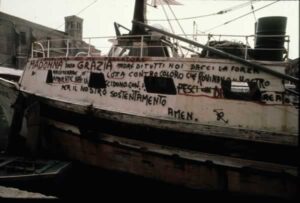

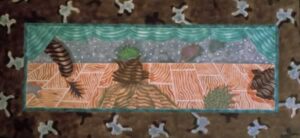

Over the years, Gilmor has returned to the ruins of ancient religions in Greece, Italy, Egypt, and Japan (Booda Doo-da) and New York City (Terrorist Kitty at The Manhattan Bridge), where she has staged her performance/rituals. These cat-headed women in loose, flowing garb represent “the female psyche as a strong creative force”, while taking a tongue-in-cheek look at the way contemporary society associates animal images with gender characteristics. By incorporating satire and melodramatic gesture, the viewer is challenged into recognition of these stereotypes, and a subsequent questioning of their validity. Gilmor conceives myths as “created throughout our lives by day-to-day experiences and by the culture in which we live.” Our routine behavior can be seen as ritualistic; material objects in our culture have developed the status of shrines: significant others are “worshipped”; we create, in a sense, a unique religion of which we alone comprise the congregation. Ti is the realization of this mythic quality of our lives that Gilmor strives for in her work.

Paul Brenner, assistant curator Great Goddesses: Sculpture and Photo Tableaux by Jane Gilmor Real Art Ways, Hartford, Ct. 1988

Jane’s art is consistent in its preposterous counter play of the fashionable and the enduring concerns from Baudelaire in that her sense of the enduring is not connected with the beautiful. Instead, it is curiously intermeshed with what she also sees as slightly bizarre — ancient myths, rituals, and folk customs. She forces our recognition of the intervention of these enduring forms into contemporary culture, mass media, social fads and social ills. The success of her work comes from the precise mixture of archeological and/or anthropological research, a slightly shocking juxtaposition of this information with remnants of our multi-media world and usually a reasonable dose of humor. To do this she needs to keep a sharp eye on both the past and the present in the world around her, and the engagement and distance of the concerned commentator.

Sherry Buckberrough, Ph.D. Professor and Chair, Art History Department Hartford School of Art, University of Hartford, West Hartford, CT. 1991

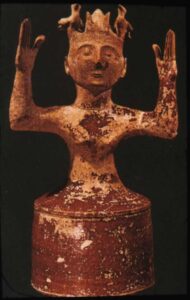

Mixing the mythic and the prosaic, Gilmor is out to mine the resonances for archetypal figures and situations in the contemporary works. Wall altars seem familiar but just out of reach. Her monumental floor pieces, resembling tombs or gravestones, tend towards more complexity: One has dozens of nude figures with animal heads hammered in relief on its metal surface; another incorporates a small television monitor with a videotaped performance. Both formats evince Gilmor’s fascination with both Christian and pagan – especially early Egyptian – imagery. The recurring figure in many of these works is a woman with the head of a cat derived from an Egyptian Goddess.

David McCracken, “Group show proves Artemisia’s Insight” Chicago Tribune, Friday October 20, 1989

Gilmor tells us we cannot glibly glorify goddess traditions without critical understanding, and clarifying our link to the past and our place in the future won’t be simple. The Book of Life contains a video of a ritualistic dance. A woman in a cat costume taps her heels, the repetitive movement seemingly without purpose. Mocking what might be a present-day temple hetaera. Gilmor questions the cultural construction of gender. She seems to say that human impulses toward religion are simultaneously absurd and meaningful, important and egocentric. We may laugh at the spoof on religious pomp and circumstance, but remain frustrated by the uncertain message.

Elise La Rose, “Outside New York, A.I.R. Gallery New York” Woman Artists News, winter, 1988-89 Vol 13, No4, 25-26 photo

In the Fall of 1976 I did an exhibition at Coe College in Cedar Rapids based on my experiences and collected artifacts from the 1976 All-American Glamour Kitty Pageant (see separate web site under that title). This began a long series of installations and [performances based on the Glamour kitty Altar ego.

To review: In April of 1976, I noticed an unusual form on the back of my bag of kitty litter. It was for the Eleventh Annual All-American Glamour Kitty Pageant. For the past year I had been making clothes for my cat, Ms. Kitty Glitter, as part of a feminist conceptual artwork. I took several photos of Ms. Kitty wearing her outfits (housewife, go-go girl, Indian maiden, cheerleader, bride, etc.) and entered them in the national competition. Over a period of several months, she was graduated from one of 250 regional winners, to one of eighteen semifinalists, to one of the nine finalists out of 20,000 to be flown to Miami Beach for the finals. Waverly Mineral Products who make the All-American Glamour Kitty brand litter sponsored the contest. This contest provided their main publicity for the product for a dozen years.

Ms. Glitter began to receive local and national media attention, as well as numerous prizes including a year’s supply of kitty litter, jeweled cat collars, engraved silver platters, and a TV set. As one of the nine finalists, Ms. Glitter and I were flown to Miami Beach for a week of “competitions” at the luxurious Hotel Fontainebleau. Two other events were being held at the Fontainebleau while we were there, an international conference on psychics (including academics and psychic Sybil Leet) and the annual conference for The National Organization of Little People.

Included in the week’s events were the Mouse Mobile Motorcade through downtown Miami, (nine Volkswagen Bugs from the local exterminating company painted like big mice) The Kitty Fashion Show, The Kitty Olympics, and the Coronation (emceed by former Miss Universe Pageant announcer Chuck Zinc). Sister Mary Louise from Pennsylvania won the fashion show competition. She dressed up like Pocahontas and dressed Harry, her cat, like Davy Crocket. The Grand Prize winner would get their cat’s picture on the front of the All-American Glamour Kitty brand cat litter for one year and win a trip to Philadelphia for a week’s vacation at the hotel where the first outbreak of Legionnaires Disease had occurred the week before our competition! No one really wanted to win after the outbreak. Ms. Kitty Glitter won the 1976 Ms. Congeniality Award!

Later that year I did the installation at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa and a series of performance events based on this bizarre experience. In the following years I developed a series of tableaux and performance pieces based on a cat-masked, toga-clad alter ego attempting to deconstruct everything from Pre-Classical Greek Mythology to Mary Kay Cosmetics.

In April of 1976, I noticed an unusual form on the back of my bag of kitty litter. It was for the Eleventh Annual All-American Glamour Kitty Pageant. For the past year I had been making clothes for my cat, Ms. Kitty Glitter, as part of a feminist conceptual artwork. I took several photos of Ms. Kitty wearing her outfits (housewife, go-go girl, Indian maiden, cheerleader, bride, etc.) and entered them in the national competition. Over a period of several months, she was graduated from one of 250 regional winners, to one of eighteen semifinalists, to one of the nine finalists out of 20,000 to be flown to Miami Beach for the finals. Waverly Mineral Products who make the All-American Glamour Kitty brand litter sponsored the contest. This contest provided their main publicity for the product for a dozen years.

Ms. Glitter began to receive local and national media attention, as well as numerous prizes including a year’s supply of kitty litter, jeweled cat collars, engraved silver platters, and a TV set. As one of the nine finalists, Ms. Glitter and I were flown to Miami Beach for a week of “competitions” at the luxurious Hotel Fontainebleau. Two other events were being held at the Fontainebleau while we were there, an international conference on psychics (including academics and psychic Sybil Leet) and the annual conference for The National Organization of Little People.

Included in the week’s events were the Mouse Mobile Motorcade through downtown Miami, (nine Volkswagen Bugs from the local exterminating company painted like big mice) The Kitty Fashion Show, The Kitty Olympics, and the Coronation (emceed by former Miss Universe Pageant announcer Chuck Zinc). Sister Mary Louise from Pennsylvania won the fashion show competition. She dressed up like Pocahontas and dressed Harry, her cat, like Davy Crocket. The Grand Prize winner would get their cat’s picture on the front of the All-American Glamour Kitty brand cat litter for one year and win a trip to Philadelphia for a week’s vacation at the hotel where the first outbreak of Legionnaires Disease had occurred the week before our competition! No one really wanted to win after the outbreak. Ms. Kitty Glitter won the 1976 Ms. Congeniality Award!

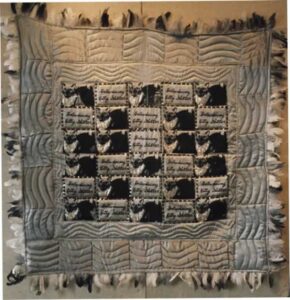

I documented this bizarre homage to America’s Cinderella Syndrome with video, photographs and a series of sculptures and installations based on Ms. Glitter’s wardrobe and the contest correspondence, events and prizes.

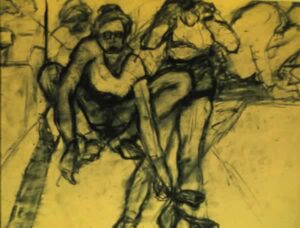

After graduating from Iowa State University in Textiles, I moved to Chicago where I studied at The School of The Art Institute of Chicago for a year while working for a team of periodontal surgeons as their bookkeeper (my only C in college). Textiles as taught at Iowa State University in the mid 1960’s had turned out to be less about artistic process and more about Home Economics.

In Chicago I encountered the art world and the work of the emerging Chicago Imagists including Jim Nutt and Gladys Nielsen. Their raw, flat, low culture imagery and their interest in so-called outsider artists like Max Yoakum had a critical impact on my work

In 1971 I returned to Iowa to get a teaching certificate from the University of Iowa. I soon wondered into the MA program in painting and began creating embroidered and stuffed paintings based on my image collection of animal stories and fairy tales (gone wrong) and Iowa State Fair freak show banners. Simultaneously, while in Iowa I was introduced to the work of Judy Chicago (who visited Cedar Rapids) and members of the West Coast “funk” movement, including Jens Morrison, William T. Wiley, Roy DeForrest and Robert Arneson. Elements of kitsch and a subversion of popular culture female stereotypes were key to my content.

The following year in graduate school at University of Iowa in Iowa City, we had professors and visitors such as Sherry Buckberrough, Lucy Lippard, and Mary Beth Edelman. Soon I (along with my friend Ana Mendieta) became deeply involved with The Women’s Art Movement of the 1970’s.

In the Early 1970’s after returning from Chicago to get a high school teaching certificate, then an MFA, I became involved in The Women’s Art Movement of the 1970’s, at first without realizing it. While teaching in Cedar Rapids, first high school, then college, I began to sponsor “parties” for my women friends to replace the usual “consciousness raising” group sessions associated with Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro’s Woman House Project at a university in southern California. First I sponsored the Tupperware Party with a real “Tupperware representative,” Jell-O mold contest and lots of demo’s. We dressed as common stereotypical images of women in society and the entire three-hour event was secretly videotaped. Our Tupperware representative seemed confused but she sold plenty (none of us really knew much about Tupperware — who could resist those popsicle makers!) We called ourselves the RPF’s (Rapid Peters Feminists) and sponsored the 1-K run from my house to the Diary Queen the next year. All winners got free Buster Bars. Eventually we took on the Great Goddess imagery at The Our Mother of Sorrows Grotto on the Mount Mercy Campus where I taught. Though this all seemed a spoof, it was meant to question The Women’s Art Movement as well as myths and stereo types about women in our culture. Though I embraced and became very active in the WAM, I found satire and humor carried more weight and garnered more attention outside the art world in a working class city like Cedar Rapids. Once I got their attention I could be more specific on what meanings I thought these images may or may not convey.

For my second year of teaching at Mount Mercy College, Kathi Pudzuvelis in the Theater Department and I created an experimental course in Women’s Performance Art and Ritual. Our final production is seen here as we hoist empty tide boxes through five feet of new snow down to the tennis court area to exorcise our secret anxieties. Unfortunately the Tide boxes were not all empty and the tennis courts were a slippery white sudsy mess then the spring thaw came. Later I used my cat masks to create a stereopticon series about Fallout shelters.

The photo tableaux by Jane Gilmor present such a startling collision of kitsch with myth that one may not know whether to chuckle or recite incantations .A masterful melange of the modern and the ancient, Gilmor’s motivations lie in “construction and deconstruction of myth;” her great goddesses enact sacred rites in the ruins of contemporary. The feline headed personae, reminiscent of vestal virgins or a kitty chorus for a Greek tragedy, appear on her sculptural assemblages and shrines engaging in their enigmatic sacraments, in miniature, in relief, in photos, and on video. As both Goddess and worshipers, these characters parody the animal associations with gender that we have come to adopt at face value in contemporary society. These works sometimes question all that we associate with modern religious pomp and circumstance, the solemnity of which seems a far cry from the performances staged by Gilmor, which blend a ceremonious melodrama with a healthy dose of satire. By incorporating satire and melodramatic gesture, the viewer is challenged into recognition of these stereotypes, and a subsequent questioning of their validity. Gilmor conceives myths as “created throughout our lives by day-to-day experiences and by the culture in which we live.” Our routine behavior can be seen as ritualistic; material objects in our culture have developed the status of shrines: significant others are ‘worshipped’; we create, in a sense, a unique religion of which we alone comprise the congregation. It is the realization of this mythic quality of our lives that Gilmor strives for in her work.

Paul Brenner, assistant curator Great Goddesses: Sculpture and Photo Tableaux by Jane Gilmor Real Art Ways, Hartford, Ct. 1988

Gilmor’s art is consistent in its preposterous counter play of the fashionable and the enduring stem (stemming from Baudelaire) in that her sense of the enduring is not connected with the beautiful. Instead, it is curiously intermeshed with what she also sees as slightly bizarre myths, rituals, and folk customs. She forces our recognition of the interventions of these enduring forms into contemporary culture, mass media, social fads and social ills. The success of her work comes from the precise mixture of archeological and/or anthropological research, a slightly shocking juxtaposition of this information with remnants of our multi-media world and usually a reasonable dose of humor. To do this she needs to keep a sharp eye on both the past and the present in the world around her, and have both the engagement and the distance of the concerned commentator.

Sherry Buckberrough, PhD. professor and Chair, Department of Art History University of Hartford, West Hartford, CT. 1991