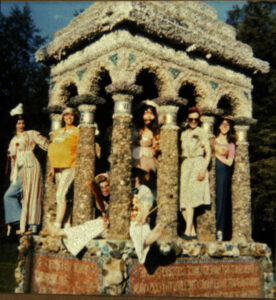

In the Early 1970’s after returning from Chicago to get a high school teaching certificate, then an MFA, I became involved in The Women’s Art Movement of the 1970’s, at first without realizing it. While teaching in Cedar Rapids, first high school, then college, I began to sponsor “parties” for my women friends to replace the usual “consciousness raising” group sessions associated with Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro’s Woman House Project at a university in southern California. First I sponsored the Tupperware Party with a real “Tupperware representative,” Jell-O mold contest and lots of demo’s. We dressed as common stereotypical images of women in society and the entire three-hour event was secretly videotaped. Our Tupperware representative seemed confused but she sold plenty (none of us really knew much about Tupperware — who could resist those popsicle makers!) We called ourselves the RPF’s (Rapid Peters Feminists) and sponsored the 1-K run from my house to the Diary Queen the next year. All winners got free Buster Bars. Eventually we took on the Great Goddess imagery at The Our Mother of Sorrows Grotto on the Mount Mercy Campus where I taught. Though this all seemed a spoof, it was meant to question The Women’s Art Movement as well as myths and stereo types about women in our culture. Though I embraced and became very active in the WAM, I found satire and humor carried more weight and garnered more attention outside the art world in a working class city like Cedar Rapids. Once I got their attention I could be more specific on what meanings I thought these images may or may not convey.

For my second year of teaching at Mount Mercy College, Kathi Pudzuvelis in the Theater Department and I created an experimental course in Women’s Performance Art and Ritual. Our final production is seen here as we hoist empty tide boxes through five feet of new snow down to the tennis court area to exorcise our secret anxieties. Unfortunately the Tide boxes were not all empty and the tennis courts were a slippery white sudsy mess then the spring thaw came. Later I used my cat masks to create a stereopticon series about Fallout shelters.

The photo tableaux by Jane Gilmor present such a startling collision of kitsch with myth that one may not know whether to chuckle or recite incantations .A masterful melange of the modern and the ancient, Gilmor’s motivations lie in “construction and deconstruction of myth;” her great goddesses enact sacred rites in the ruins of contemporary. The feline headed personae, reminiscent of vestal virgins or a kitty chorus for a Greek tragedy, appear on her sculptural assemblages and shrines engaging in their enigmatic sacraments, in miniature, in relief, in photos, and on video. As both Goddess and worshipers, these characters parody the animal associations with gender that we have come to adopt at face value in contemporary society. These works sometimes question all that we associate with modern religious pomp and circumstance, the solemnity of which seems a far cry from the performances staged by Gilmor, which blend a ceremonious melodrama with a healthy dose of satire. By incorporating satire and melodramatic gesture, the viewer is challenged into recognition of these stereotypes, and a subsequent questioning of their validity. Gilmor conceives myths as “created throughout our lives by day-to-day experiences and by the culture in which we live.” Our routine behavior can be seen as ritualistic; material objects in our culture have developed the status of shrines: significant others are ‘worshipped’; we create, in a sense, a unique religion of which we alone comprise the congregation. It is the realization of this mythic quality of our lives that Gilmor strives for in her work.

Paul Brenner, assistant curator Great Goddesses: Sculpture and Photo Tableaux by Jane Gilmor Real Art Ways, Hartford, Ct. 1988

Gilmor’s art is consistent in its preposterous counter play of the fashionable and the enduring stem (stemming from Baudelaire) in that her sense of the enduring is not connected with the beautiful. Instead, it is curiously intermeshed with what she also sees as slightly bizarre myths, rituals, and folk customs. She forces our recognition of the interventions of these enduring forms into contemporary culture, mass media, social fads and social ills. The success of her work comes from the precise mixture of archeological and/or anthropological research, a slightly shocking juxtaposition of this information with remnants of our multi-media world and usually a reasonable dose of humor. To do this she needs to keep a sharp eye on both the past and the present in the world around her, and have both the engagement and the distance of the concerned commentator.

Sherry Buckberrough, PhD. professor and Chair, Department of Art History University of Hartford, West Hartford, CT. 1991