In 1994 Lesley Wright, then curator for the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art invited me to have a solo show at the museum. Because I was heavily involved in community-based work with the disenfranchised in shelters across the country, I decided to combine my solo show with a project in Cedar Rapids working with the YWCA, The Madge Phillips Women’s Shelter and the McAuley Center for Women. Part of my goal was to get participants in both communities to cross borders. The YWCA and Madge Phillips Center were literally across the street from the Museum but neither group had visited the other’s space. My hope was to expose not only the shelter participants but also the community at large to new forms for art and the idea that use of the imagination can become a survival tool in extraordinary circumstances.

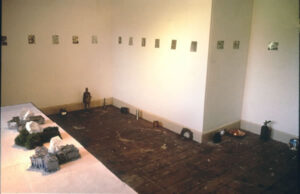

By creating installations involving all participants in both locations and providing free admission and transportation, I hoped to encourage the shelter participants to enter the museum and vice versa. The YWCA provided me with their Board Room and their large glass storefront for the installation there. The Museum gave me an entire floor and let me break a few rules. There was a gala opening at both venues and an active exchange of comments by virtue of a Thank You Shrine in the Museum where people could leave notes and “things” or take them.

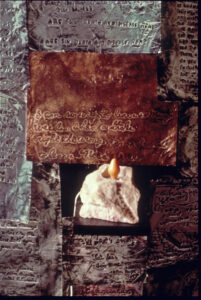

The idea of working with the contrasts of the privileged versus the disenfranchised had developed the year before while I was in residence at the Tyrone Guthrie Center Artist Colony in Ireland. My room and studio were in the Guthrie Mansion, where the halls and walls were filled with valuable artifacts. The irony of being paid a stipend to be in a beautiful place and work with my collected notes from homeless individuals resulted in my installation Ireland. I collected silver and gold artifacts from the hallway and library display cases and sat them on the floor of my empty room. Mounted on the wall above each was a 5″ x 7″ metal note incised with words or images from homeless adults and children. Under the window in the room I placed a long dinner table. On a ledge under the table I placed three white dinner plates, each with a large potato housing a 4-inch gas flame. On the table above, directly above each potato I placed a cross-shaped Kleenex box holder – one covered in living moss, one in rocks, and one with metal incised with love letters.

The 1994 exhibitions and events at The YWCA and the Cedar Rapids Museum grew from this concept and included continued references to beds, shelter and loss of identity. In particular, the YWCA Board room offered a site similar to the Ireland piece in that it housed the valuables of their collection and was designed with for the more privileged board members, but stood just down the hall from a shelter for abused women and children.

As her work has matured, Gilmor has continued to reflect on contemporary and developing feminist art discourse. As she and many other privileged American women artists consider their advantages, they have examined issues of the disadvantaged, as Gilmor has with her projects about and with homeless people. As issues of women’s identity have expanded to include the immigrant and the eroticized other, she has enlarged her practice to include collaborations, new combinations of sculpture, video/performance, her recent work, provides a good connecting thread to the contemporary practice of Midwestern American women artists and their present work on identity, process and labor, bearing witness to and questioning history.

Jayne Hileman, Professor of Art, St. Xavier University, Chicago, From the lecture: Women Artists At Work in Chicago 2000-2005