Jane Gilmor: Statement August 2018

Two months ago, driving my little KIA back from a California residency, the Great Salt Lake appeared. Loaded down with a new series of wearable whatevers, I visualized dragging myself across this salt desert with a small band of women, all of us wearing versions of my latest getups.

Back home an email from Prompt inviting me to create a visual response to Rachel Yoder’s essay The Traditional Room.

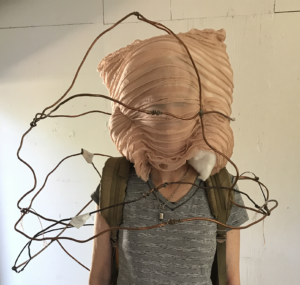

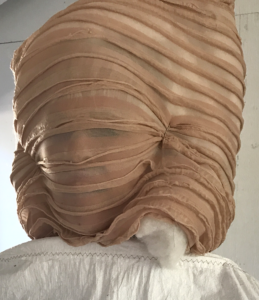

An amalgam of cultural critique and intuitive response to personal experience, my Containers for the Self are wearable structures investigating those entanglements of image, language and space through which we try to locate our own identity. Depriving the wearer of touch, vision, and mobility, they explore the dualities of presence/ absence, public/private, poverty/privilege, or female/male through found materials and forms. The search is for some unspoken connection in these random collisions.

The following is Rachel Yoder’s essay “Prompt”:

Rachel Yoder

The Traditional Room

The double skirt began as a regular, single, knee-length skirt, worn in the traditional manner in a traditional sort of room. However, there were those who came to object to such a skirt and the type of women who wore it. “They routinely hitch it up and pin the cloth to form abbreviated skirts,” the newspapers quoted. “It is waved to and fro in the manner of can-can dancers. See how the women flit on stage or sidewalk in their skirts with all parts of their bodies showing: their shins and the fleshy parts above their knee caps. Elbows. Their necks.” There was a great exodus of women to another room in which skirts were actually banned and alternative modes of clothing supported. There such things as parachutes, umbrellas, kites, flags, and sails flourished as forms of fashion.

However, back in The Traditional Room, the regular, single, knee-length skirt was legislated into a double skirt, two knee-length skirts worn at the same time, the outer skirt meant for the lifting and the covering of the face in moments of great blushing or fear or what have you. Some also viewed this as a gesture of piety or modesty, or pious modesty, and thus it became a religious act. Sects grew up in which the double skirt was worn continuously, pulled up round the faces of shy, pretty women. The act itself, however, of raising one’s double skirt was viewed by believers as overtly pornographic and so the upper skirt was raised privately before a pious woman went out, in her bedroom or perhaps even in the closet of her bedroom or even in the far recess of her long closet: this is where she took the hem between her fingers and floated it to her face and, in some cases, up over her head and down her back in a long veil. The double skirts grew.

Whole schools of women walked the streets dragging miles of cloth in their wake. On hot days, those prone to asthma or panic suffocated from the fabric pulling against their faces and then fell. Others crouched at their sides and felt for the heads of the fallen. The pious women could not see while wearing the double skirts but this, they felt, was a perfect sort of holiness. They pulled at the double skirts covering the faces of the women lying on the sidewalks until they could stand and breathe.

The double skirt swept up with it dead leaves and grass clippings, glinting shards of glass and lost earrings. Sometimes even small animals such as lice, flies, frogs, or grasshoppers were taken into the double skirts and at night, when the women pulled the skirts from their faces, the plagues were invoked in their bedrooms. Swarms ate holes through their wardrobes. They could not go out for fear of being seen. Others were left empty eyed on their beds, a barrage of flattened and rotting frogs at their feet. The walls moved with flies. Lice hid in their hair. Some had caught up the carcasses of birds and left streaks of brown blood in their sheets.

The schools of women on the streets thinned. Those who remained refused to remove the double skirts from their heads. Great sores formed on their faces and bodies from the rubbing. Others, on seeing the thinning of the schools, insisted on cladding their pets in double-skirts, and soon dead dogs and horses wrapped in lengths of fabric dotted the countryside. Pious hysteria became a diagnosable condition and various women were sent away to other rooms wherein they might receive treatments of moist, diaphanous cloths.

A rogue band of women became possessed of incomprehensible urges. They felt the times were slipping from them and, in an effort to regain control, crafted vast insurgent skirts which they used to control the weather, flying them from massive poles. Prevailing winds no longer prevailed. Great clouds formed and moved over land masses then dropped ice on the land. In a final statement, the rogue women launched skirts to space stations and deployed them over huge swaths of Earth.

Monstrous shadows which conjured monstrous mothers blinded The Traditional Room and other rooms both like and unlike it in darkness. De-greened wastelands spread. The Earth wore skirts of dust for many years, and the pious women migrated to these deserts. There, after many centuries, they discarded their double skirts and became naked, having forgotten their origins. They were not ashamed.

Rachel Yoder is the author of award winning novel Nightbitch, Doubleday, 2021, which has been translated into 14 languages. It was named best book of the year by Vulture and Esquire and recognized by the PEN/Hemmingway Award and shortlisted for the McKitterick Prize. She is a founding editor of draft: the journal of process which published first and final drafts of stories, essays, and poems along with author interviews about the creative process. Her essays and stories have appeared in The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, The Paris Review Daily, and The Sun Magazine, among many other print and online publications. She directs literary programming for the Mission Creek Festival in Iowa City and holds an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from the University of Iowa as well as an MFA in Fiction from the University of Iowa.