The totality of this work is extraordinary. It is my good fortune to have seen, touched and sensed this piece of art.

Ann Hamilton, artist, 4/20/99 Guestbook, Windows ’95, Des Moines Art Center)

Both Windows 95 and Wisdom Passage is were non-profit community arts projects intended to expose participants and the general public to one approach to what critic Arlene Raven has called new genre public art or art in the public interest.

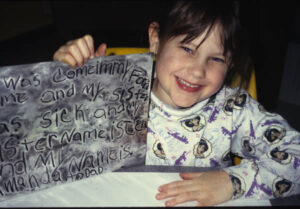

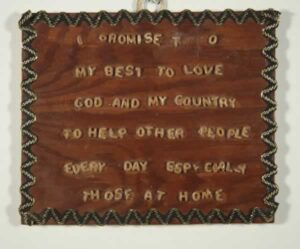

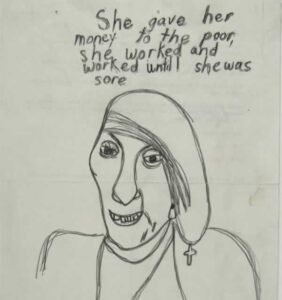

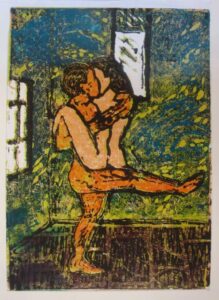

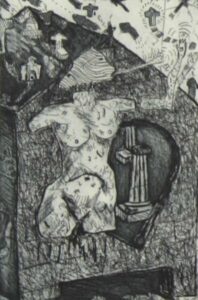

Both projects are collaborative projects intended to give seriously ill hospitalized children or adults access to nontraditional art forms for personal expression and to encourage use of the imagination as both a survival tool and as a means for creating a psychological home away from home. It is my belief that art can help make meaning of one’s experiences, particularly when those experiences interrupt everyday life.

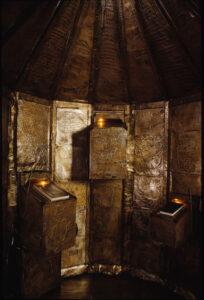

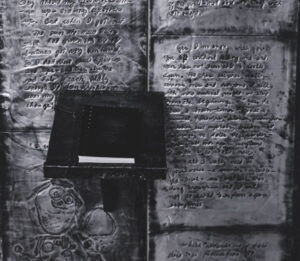

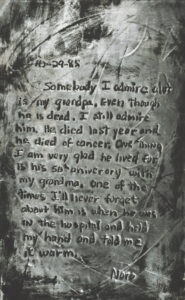

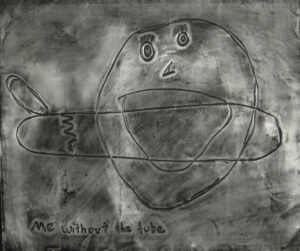

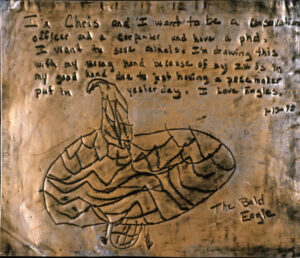

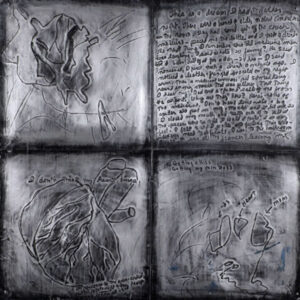

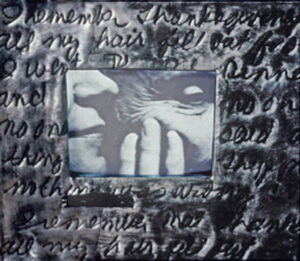

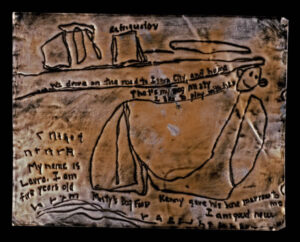

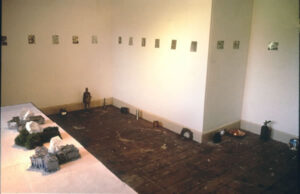

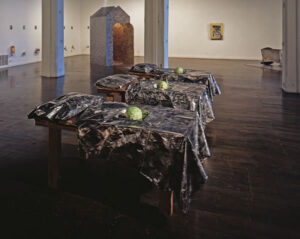

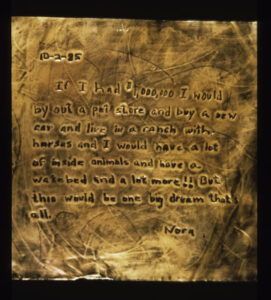

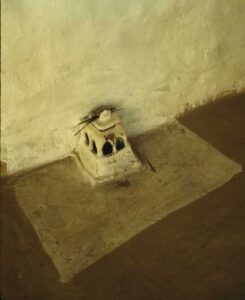

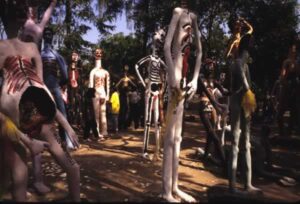

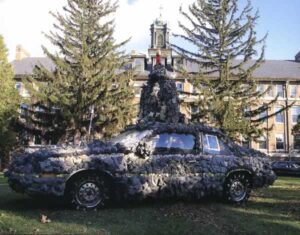

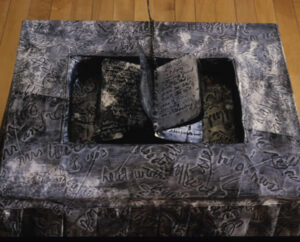

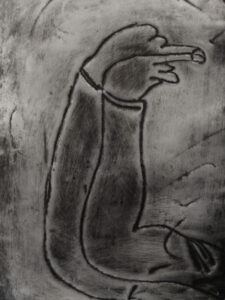

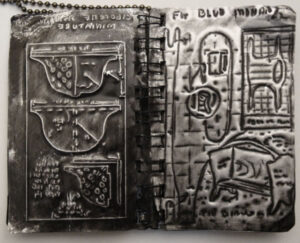

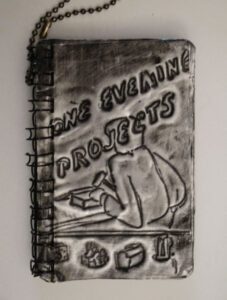

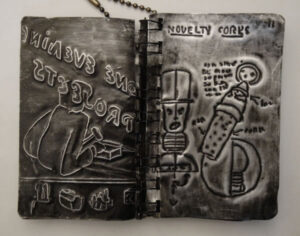

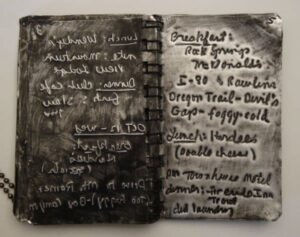

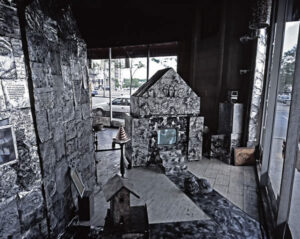

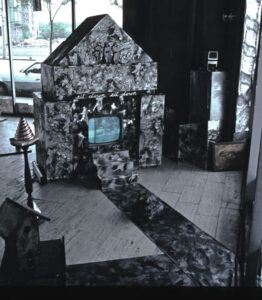

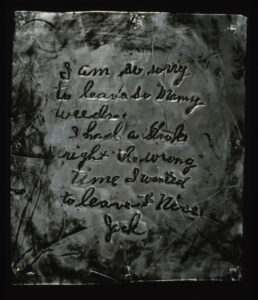

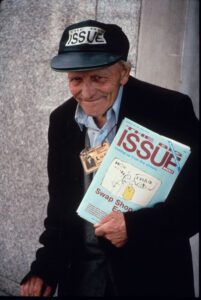

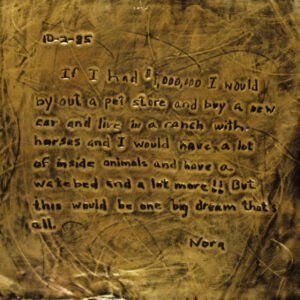

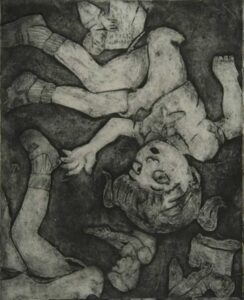

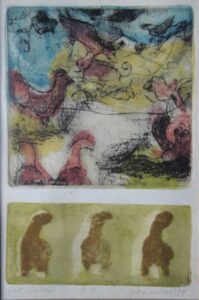

Windows 95 is owned by The Des Moines Art Center and was funded by a grant from The Iowa Arts Council and The University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. This collaborative work takes the form of a large, walk-in structure (built by artist Rick Edelman), covered inside and out with words and images on metal. In a series of weekly workshops over a one-year period, children from the Child Life Program of The Activities Therapy Department at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics were invited to create images and writing related to their experiences, feelings and fantasies while hospitalized. Since UIHC is a state medical facility, children came from variety of economic and social backgrounds. The equalizer was serious illness. Monitors on the outside of the structure show video images, created by participants, of individual children looking out an imaginary window. Once inside the sculpture viewers are invited to contribute their own written stories, comment images. This work was is the lobby of the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City for two months in 1996.

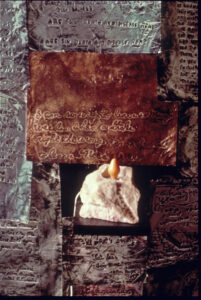

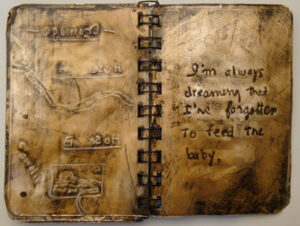

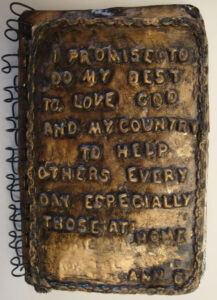

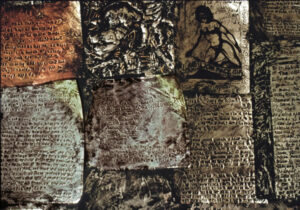

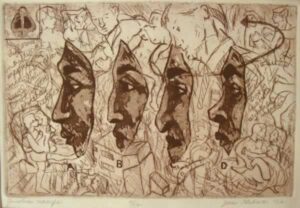

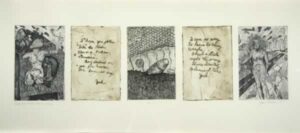

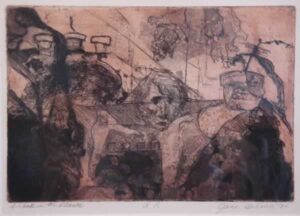

Wisdom Passage, 1996-7 is the result of collaboration between nationally known artists Jane Gilmor and Sandra Menefee-Taylor and oncology patients and their families from St. Paul/Minneapolis and Sioux City. In a series of workshops participants at St. Joseph’s Hospital in St. Paul were invited to keep journals concerning their experiences, feelings, and fantasies while struggling with serious illness. Writings and drawings selected from these journals by the participants were then transferred onto metal and plaster panels by Gilmor and Menefee-Taylor. The large bridge-like sculpture itself was designed by Gilmor and constructed by artist Rick Edelman. The videotape appearing on small window monitors was collaboration between Menefee-Taylor and award-winning Minneapolis filmmaker Kathleen Laughlin.

The Wisdom Passage Project was created in cooperation with the HealthEast Oncology Program in Minneapolis/St. Paul. Funding was provided by an Intermedia Arts/McKnight Interdisciplinary Artist’s Fellowship to Jane Gilmor. All participants are given extensive credit for their contributions. Any profits were used to help pay for uncovered costs of the project.

Thank you to all those who participated in both projects, many of whom have signed their work. Thank you also to those who have chosen to remain anonymous, but who are not forgotten.