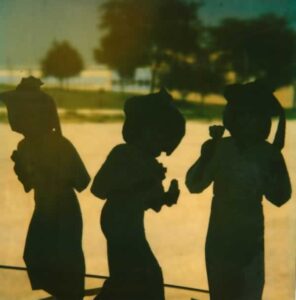

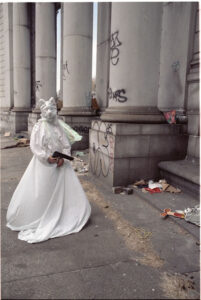

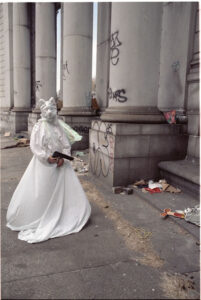

Terrorist Kitty At the Manhattan Bridge, performance, photo tableau, NYC, 1986

Terrorist Kitty at the Manhattan Bridge with Pinocchio’s Better Half, NYC 1986

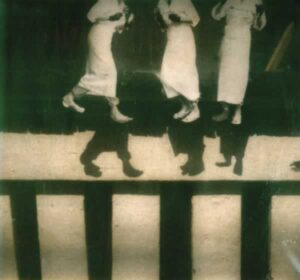

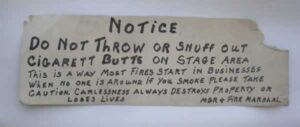

Terrorist Kitty at Freight Salvage, photo tableau, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, 1985

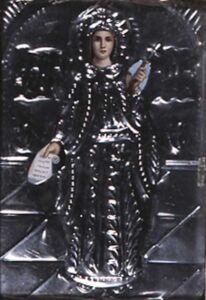

Erma’s Apparition of Her Greatness at Maple Lanes, photo tableau, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, 1985

Erma’s Apparition of Her Greatness, Grand Lodge of Iowa, Cedar Rapids, 1985

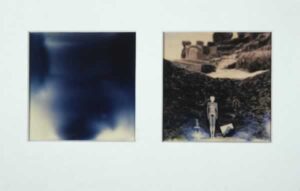

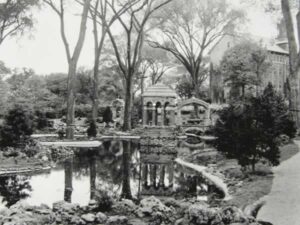

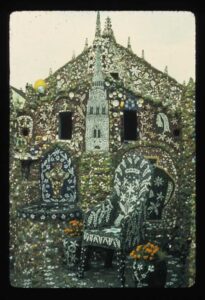

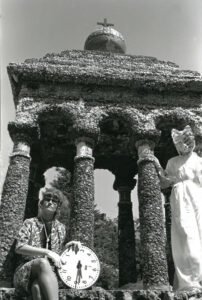

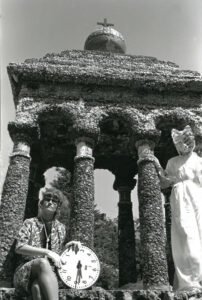

Erma and Her Greatness at the Grotto, Our Mother of Sorrows Grotto, Mount Mercy College, Cedar Rapids, Iowa 1984-5

Erma and her greatness at the Laundromat, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, 1985

Erma and the Big Rooster, rural Iowa, 1984

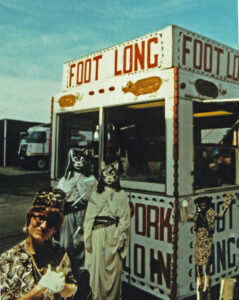

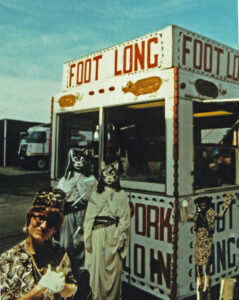

Erma and Kitty at the Fair, Cedar Rapids, Iowa 1985

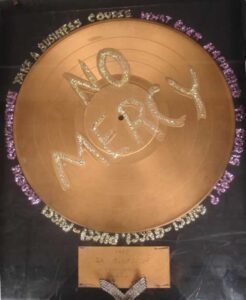

Erma deconstructs Time, Religion and Liberty, photo tableau, Rod Bradley studios, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, 1986

Erma and The 1976 All-American Glamour Kitty Deconstruct, Rod Bradley studios, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, 1986

Postmodern impulses: Kitty Liberty Reconsiders her Heritage, Rod Bradley studios, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, 1986

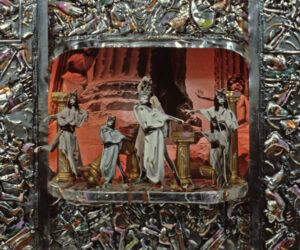

Erma presents the Imperial Potentate, tableau, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, 1985

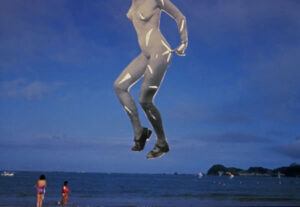

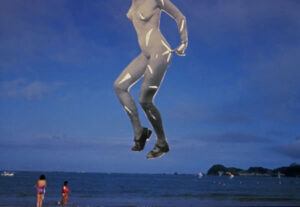

The 1976 All-American Glamour Kitty at the Beach, Acapulco, Mexico, 1984

Ms. Kitty Glitter at the Beach, Acapulco, Mexico, 1987

1980’s Performance/ tableaux

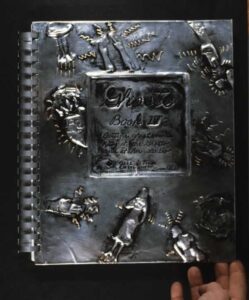

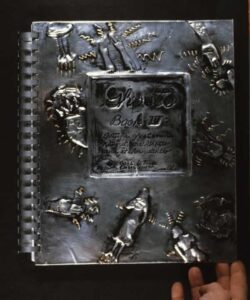

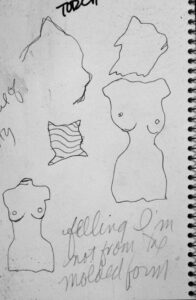

My work with photo tableaux and performance began in the mid 1970’s with the All-American Glamour Kitty Pageant and my subsequent adoption of a cat-masked Isadora Duncan like Great Goddess archetype performing and reclaiming ancient ruins sites in Greece, Egypt, and Turkey. I use tableaux as a framing device in arranging symbols to convey or to question meaning. In the early 80’s, collaborating again with my colleague in theater, Kathi Pudzuvelis, a new character entered into these tableaux — Erma. Based on my sixth grade math teacher, Erma is the quintessential “modern” (not postmodern) woman. The cat Goddess often appears to be shadowing her as if questioning the nature of stereotypes being created by these images. Erma’s state of confusion and skepticism is also intended to raise questions that might force us to “deconstruct” these images.

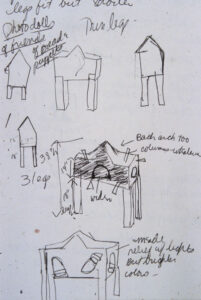

Erma first appears in tableaux set in Cedar Rapids, Iowa bowling alleys and laundromats. When not present in person, photo dolls, like those used in some of the Greek performance tableaux of the 70’s, fill in. From the Early 80’s on photo dolls of the cat Goddess, Erma and my friend Betty Booda, West Coast artist Ann Gerber Sakaguchi, (representing the Eastern tradition) traveled with me everywhere. The Isadora Duncan Cat mask costume came along as well.

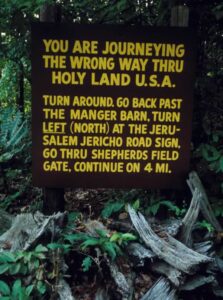

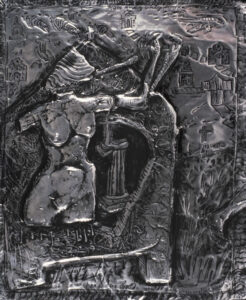

In 1986, after taking on the Midwest and Japan, I lived in New York City for a year. On the Lower East Side, I literally lived among the ruins of the Manhattan Bridge as it was being partially rebuilt. Continuing my investigation of contemporary cultural icons (Statue of Liberty, Mickey Mouse, and the new breed of “terrorist”) I created a series of images that seem strangely ominous today (particularly the image of Terrorist Kitty” with the Trade Towers in the background, 1986). Images of the statue of Liberty also figure prominently in a series of tableaux done later using Erma, and the cat goddess at a Grotto folk Art Site on the Mount Mercy College campus. Addressing the tenth anniversary of the U.S. Bicentennial as well as contemporary postmodern criticism in arts and architecture, Erma looks confused!

Comments from reviewers:

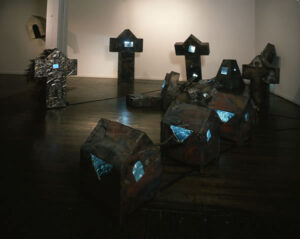

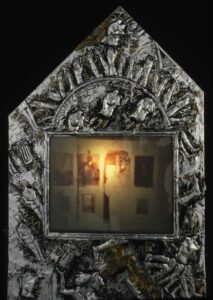

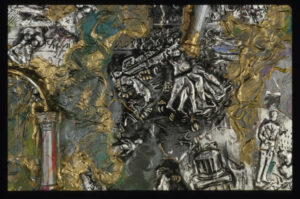

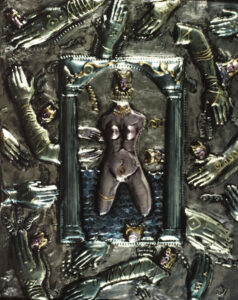

The photo tableaux by Jane Gilmor present such a startling collision of kitsch with myth that one may not know whether to chuckle or recite incantations. When Erma confronts the Great Goddess, one can’t help but wonder what each must be thinking about the other. A masterful mélange of the modern and the ancient, Gilmor’s motivations lie in “construction and deconstruction of myth;” her great goddesses enact sacred rites in the ruins of temples, counterparts to the rituals that must have once taken place there in honor of mythological deities. The feline headed personae, reminiscent of vestal virgins or a kitty chorus for a Greek tragedy, appear on her sculptural assemblages and shrines engaging in their enigmatic sacraments, in miniature, in relief, in photos, and on video. As both Goddess and worshipers, these characters parody the animal associations with gender that we have come to adopt at face value in contemporary society. These works question all that we associate with modern religious pomp and circumstance, the solemnity of which seems a far cry from the performances staged by Gilmor, which blend a ceremonious melodrama with a healthy dose of satire.

Recent tableaux present Erma, the typical “modern” woman as tourist and woman-of-the-world — bowling in white gloves and shadowed by a Great Goddess. In performance photos from “Erma Deconstructs Time, Religion, and Liberty,” a Great Goddess in the Guise of the iconic Statue of Liberty stands monumentally beside the screen, which presents a changing chronicle of Erma’s experiences. All the While Erma herself enacts ritualistic movements and a clock operates as a referent for Erma’ life. By incorporating satire and melodramatic gesture, the viewer is challenged into recognition of these stereotypes, and a subsequent questioning of their validity.

Gilmor conceives myths as “created throughout our lives by day-to-day experiences and by the culture in which we live.” Our routine behavior can be seen as ritualistic; material objects in our culture have developed the status of shrines: significant others are ‘worshipped’; we create, in a sense, a unique religion of which we alone comprise the congregation. It is the realization of this mythic quality of our lives that Gilmor strives for in her work.

Paul Brenner, assistant curator Great Goddesses: Sculpture and Photo Tableaux by Jane Gilmor Real Art Ways, Hartford, Ct. 1988

Gilmor’s art is consistent in its preposterous counter play of the fashionable and the enduring stem (stemming from Baudelaire) in that her sense of the enduring is not connected with the beautiful. Instead, it is curiously intermeshed with what she also sees as slightly bizarre ancient myths, rituals, and fold customs. She forces our recognition of the interventions of these enduring forms into contemporary culture, mass media, social fads and social ills. The success of her work comes from the precise mixture of archeological and/or anthropological research, a slightly shocking juxtaposition of this information with remnants of our multi-media world and usually a reasonable dose of humor. To do this she needs to keep a sharp eye on both the past and the present in the world around her, and have both the engagement and the distance of the concerned commentator.

Sherry Buckberrough, PhD. professor and Chair, Department of Art History University of Hartford, West Hartford, CT. 1991